Notes from the development of xkcd's "Pixels"

Over the years, I’ve had the pleasure of hacking on the frontend code for a bunch of xkcd’s interactive comics, including: unixkcd, xk3d, Umwelt, Time, Externalities, and Lorenz. This weekend, I was pinged about making something to coincide with the release of What If?: Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions. The process of building “Pixels” was even crazier than our usual April Fools rush, and had the extra intrigue of being live during Randall Munroe’s Colbert Report interview.

Here’s a few anecdotes from the development of Pixels and a quick explanation of how it works. I hadn’t worked with some of the graphics programming patterns (coordinate systems!) for a while, so I ended up making some classic mistakes — hopefully you can avoid repeating them. :)

background

Pixels is an infinitely zoomable black-and-white comic. As you zoom in, the pixels that make up the image resolve into smaller square comic panels — dark ones for black pixels, light ones for white. Depending on which panel you are looking at, the set of pixel panels will be different. These comics can be further zoomed into, revealing new pixels, ad infinitum.

view the source code on GitHub

Our schedule for the project was pretty absurd: we had 3 days from the first discussions on Saturday to going live Tuesday night. I was traveling between 3 different states during those days. With this crazy schedule, there was very little margin for error or engineering setbacks. I ended up sleeping for a total of 1 hour between Monday and Tuesday, finishing the zooming code on a plane flight home to SF via Gogo Inflight Internet. My plane landed in SFO a half hour before our rough goal of launching midnight EST. While my cab was hurtling me home at 80mph, the folks at xkcd were putting the final touches on the art and server code. We cobbled it all together over IRC and went live at around 1:30am EST.

On the art side, we decided on a panel size of 600x600, with pixels only pure black or pure white. Without grays for antialiasing, the images look a little crunchy to the eye, but this makes the zoomed pixels faithfully match the original image (we also thought the crunchiness would be a nice cue that this comic was different from the usual). On the tech side, HTML5 Canvas was the obvious choice to do the drawing with decent performance (I also tested plain <img> tags and found they were significantly slower). Unfortunately, browsers were still too slow to draw all 360,000 individual pixel panels via Canvas, so we had to compromise for fading the individual pixels in once they were 500%-1000% zoomed.

For this project, I chose to use vanilla JavaScript with no external dependencies or libraries. In general, we strive to keep the dependency count and build process minimal for these projects, since keeping the complexity level low gives them a better chance of aging well in the archives. Browsers recent enough to support Canvas (IE9+, Firefox, Chrome, Safari) are superficially consistent enough to spec to not require too much time fixing compatibility issues.

to infinity and beyond

One of the core challenges to Pixels was representing the infinitely deep structure and your position within it. As you zoom in, the fractal pixel space is generated lazily on the fly and stored persistently, so that when you zoom back out, everything is where you first saw it.

Each panel has a 2d array mapping: a pixel stores the type of panel it expands to, and possibly a reference to a deeper 2d array of its own constituent pixels. Appropriately, this data structure is named a Turtle, a nod to the comic and “Turtles all the way down”.

To represent your position within the comic, it would be convenient to store the zoom level as a simple scale multiplier, but you’ll eventually hit the ceiling of JavaScript’s Number type (as an IEEE 754 Double, that gives you log(Number.MAX_VALUE, 600) ≈ 111 zoom nestings). I wanted to avoid dealing with the intricacies of floating point precision, so I decided to represent the position in two parts:

pos: a stack of the exact panel pixels you’ve descended intooffset: a floating point position (x, y, and scale) relative topos

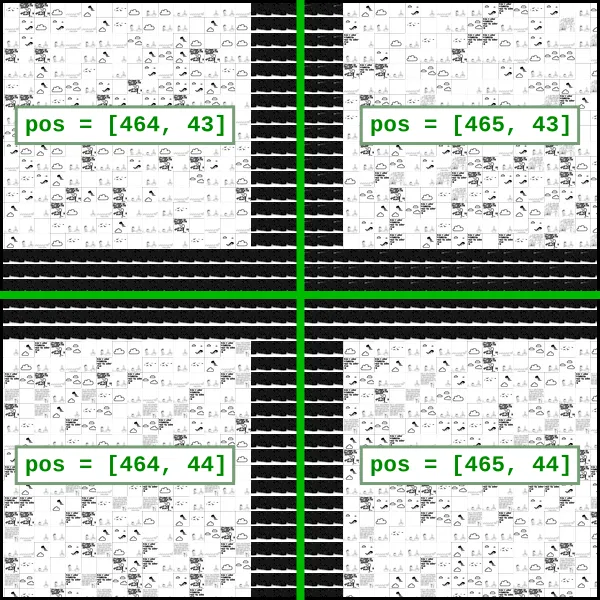

Here’s a couple examples:

![]()

To render the comic, we locate the Turtle that accords to pos and draw the pixels described in its 2d array, offset spatially by the values of offset. As you scroll deeper, pos becomes a long array of the nested pixels you’ve entered, like [[305, 222], [234, 674], [133, 733], ...]. When you zoom far enough to view the pixels of a panel for the first time, the image data is read using a hidden Canvas element, and a new Turtle object is generated with the panel ids for each pixel.

One complexity of relying on pos for positioning is that it needs to update when you zoom into a panel / out of panel / pan to a different panel. When a pixel panel is zoomed in past 100% size, its location is added to the pos stack, and offset is recalculated with the panel as the new point of reference. Some of the hairiest code in this project came down to calculating the new values of offset.

There’s a small trick I used to simplify the handling of the various cases in which pos needs to be updated. If the current reference panel is detected to be offscreen or below the 100% size threshold, pos and offset are recalculated so that the point of reference is the containing panel, as if you were zoomed in really far. This then triggers the check for “zoomed in past 100% size”, which causes a new reference point to be chosen using the same logic as if you’d zoomed to it.

corner cases

Working out the browser and math kinks to simply position and draw a single Turtle took way longer than expected. It took me deep into the second night of coding to finish the scaffolding to render a single panel panned and zoomed correctly. Then, I needed to tackle nesting. Because the sub-panels are pixel-sized, you can’t see the the individual pixel panels until you zoom above 100% scale. Since a panel at 100% scale takes up the whole viewing area, I initially thought this implied I’d only need to worry about drawing the pixels for a single panel at a time.

I then realized a problem with that thinking: if you zoom into a corner, you can go past 100% scale with up to 4 different panels onscreen:

This thought led me to make the worst design decision of the project.

TurtlesDown.prototype.render = function() {

// there is no elegance here. only sleep deprivation and regret.

Brain-drained at 3am, and armed with the knowledge that there could be up to 4 panels onscreen at any time, I began to write code from the perspective of where those 4 panels would be. I decided to let pos reference the panel at the top-left-most panel onscreen, and then draw the other 3 panels shifted over by one where appropriate.

For me, programming late at night is dangerously similar to being a rat in a maze. I can follow along the path step-by-step well enough, but can’t see far enough down the line to tell whetcher I’ve made the right turn until it’s too late. With proper rest and a step back to think, it’s clear to see what’s going on, but in the the moment when things are broken it’s tempting to plow through. Once I got 4 panels drawing properly, I realized the real corner case:

Consider that the top left panel has position [[0, 0], [599, 599]]. How do we determine what the other 3 panels will be? We can’t just add one to the coordinates. We have to step back up to the parent panel, shift over one, and wrap around. In essence, we have to carry the addition to the parent. And, if necessary, its parent, and so on…

At this point, I needed to get something working and was too far down the path to reform the positioning logic into what it should have been: a descending recursive algorithm. Walking the pos stack and doing this carry operation iteratively ballooned into 40 lines of tough to reason about code. It’s necessary to carry the x and y coordinates separately — this is something I forgot to account for in an early release, causing some fun flicker bugs at certain corner intersections.

I’m not proud of the render() function or how it turned out — but I’m really happy and somewhat bemused that when all is said and done, that nightmare beast seems to work properly.

”I’m not sure how this works, but the algebra is right”

Like many computer graphics coordinate systems, Canvas places (0,0) in the top-left. Early on I decided to translate this so that the origin was in the center, in order to simplify zooming from the center of the viewport (centerOffset = size / 2). A while later, I discovered that the simple ctx.translate(centerOffset, centerOffset) call I was using didn’t apply to ctx.putImageData(), the main function used to draw pixel panel images. I considered two options: either I could figure out the geometry to change my zooming code to handle an origin of (0,0), or manually add centerOffset to all of my putImageData() calls and calculations. I did the latter because it was quick. That was a mistake.

What I didn’t foresee was how much splattering centerOffset everywhere would increase the complexity of the equations. The complexity arises when centerOffset is multiplied by offset.scale or needs to be removed from a value for comparison. For example (from _zoom(), which ended up needing to know how to origin shift anyway!):

// ugh.

this.offset.x =

((this.offset.x - centerOffset) * this.offset.scale - scaleDeltaX) /

this.offset.scale +

centerOffset

In general, it’s a good idea to do your translate operation as late in the chain as possible. Eliminating or externalizing as many operations as possible helps keep things understandable. I knew better, but I didn’t see the true cost until it was too late…

Eventually, the complexity of some of my positioning code reached the point where I could no longer think about it intuitively. This led to some very frustrating middle-of-the-night flailing in which I sorta understood what I needed to express mathematically, but the resulting code wouldn’t work properly. The approach that finally cracked those problems was going back to base assumptions and doing the algebra by hand. It’s really hard to mess up algebra, even at 5am. However, this had the amusing consequence of me no longer grokking how some of my own code worked. I still don’t understand some of the math intuitively, sadly.

TV audiences are mobile

All told, our launch went quite well. While there were some timing and performance issues we noticed the following day, it seemed to work for most people — a huge relief after the last 2 days. I spent Wendesday working through my backlog of minor fixes and improvements in preparation for the Colbert Report bump. Two tasks I triaged for release were proper IE support and mobile navigation. For IE, due to the lack of support for cross-origin canvas image reading, we needed to do some iframe silliness to get IE to work properly. Regarding mobile, I didn’t think that phone browsers would perform very well on the image scaling, so I deferred it to focus on the best experience.

We anticipated a higher proportion of the Colbert Report referrals would be using IE, so we sprinted on that, getting it working just in time before the xkcd folks needed to leave for the interview. However, rushed nerds as we were (and ones who usually do not watch much TV), we didn’t consider a very important aspect:

People watching TV don’t browse on computers. They use their phones.

As I watched the traffic wave arrive via realtime analytics, my heart sank. The visitors were largely mobile! A much, much larger proportion than those using IE. Our mobile experience wasn’t completely broken, but if we’d been considering the mobile traffic from the start, we’d have focused on it a good deal more.

berzerking works (sometimes)

When working fast, you have to resign yourself to make mistakes. Trivial mistakes. Obvious ones. Some of those mistakes can be slogged through, while some will bring a project down in flames. There’s a delicate calculus to deciding whether a design mistake is worth rewriting or being hacked around. Having a hard 2 day deadline amplifies those decisions significantly.

I, like most developers I know, hate the feeling of a project running away from me; hacking blindly and not fully understanding the consequences. That’s how insidious bugs are absently created, or codebases that need to be scrapped and rewritten from scratch. I prefer to take the time to recognize the nature and patterns to my problems and realize them with elegance.

Yet — sometimes, for projects small enough to fit fully in the head, and rushed enough to not weather a major time setback, brute force crushing works. For fleeting art projects that are primarily to be experienced, not maintained, that is perhaps enough.

When we work on interactive comics at xkcd, we take pride in experimenting with the medium. It’s a privilege to combine forces with their masterful backend engineer + Randall Munroe’s witty and charming creativity. Each collab is an experiment in what kinds of new experiences we can create with our combined resources at our disposal.

One of the fun aspects of working with comics is you don’t expect them to think, to react to your behavior, to explore you as you explore them. That lack of expectation allows us to create magic. Every now and then, it’s good to shake things up and push the near-infinite creative possibilities we have on the modern web. The health and sanity costs on these projects are high, but for me personally, novelty is the impetus to take part in these crazy code and art dives.

Overall, my favorite part of working on these projects is the moment after Randall’s art & creative comes in: when I get to experience the project for the first time. Even though I know the general mechanic of the comic, when the backend, frontend, art, and humor all click into place simultaneously, it becomes something new. That first moment of discovery is as much a joy and surprise to me as it is to you.